Blog

December 2, 2025

Jim WagnerWhen Should We Tell Research Participants About AI? The Emerging Consensus on Disclosure in Clinical Trial Informed Consent

A growing consensus says research participants should be told how AI shapes their trial experience—and why it matters.

Key Takeaways

If the FDA trusts its new “Elsa” AI system enough to integrate it into agency workflows—using the generative AI tool to cut three-day review tasks to mere minutes—maybe the question isn’t whether we can use AI in clinical research, but rather how transparently we should communicate that use to the people who matter most: research participants.

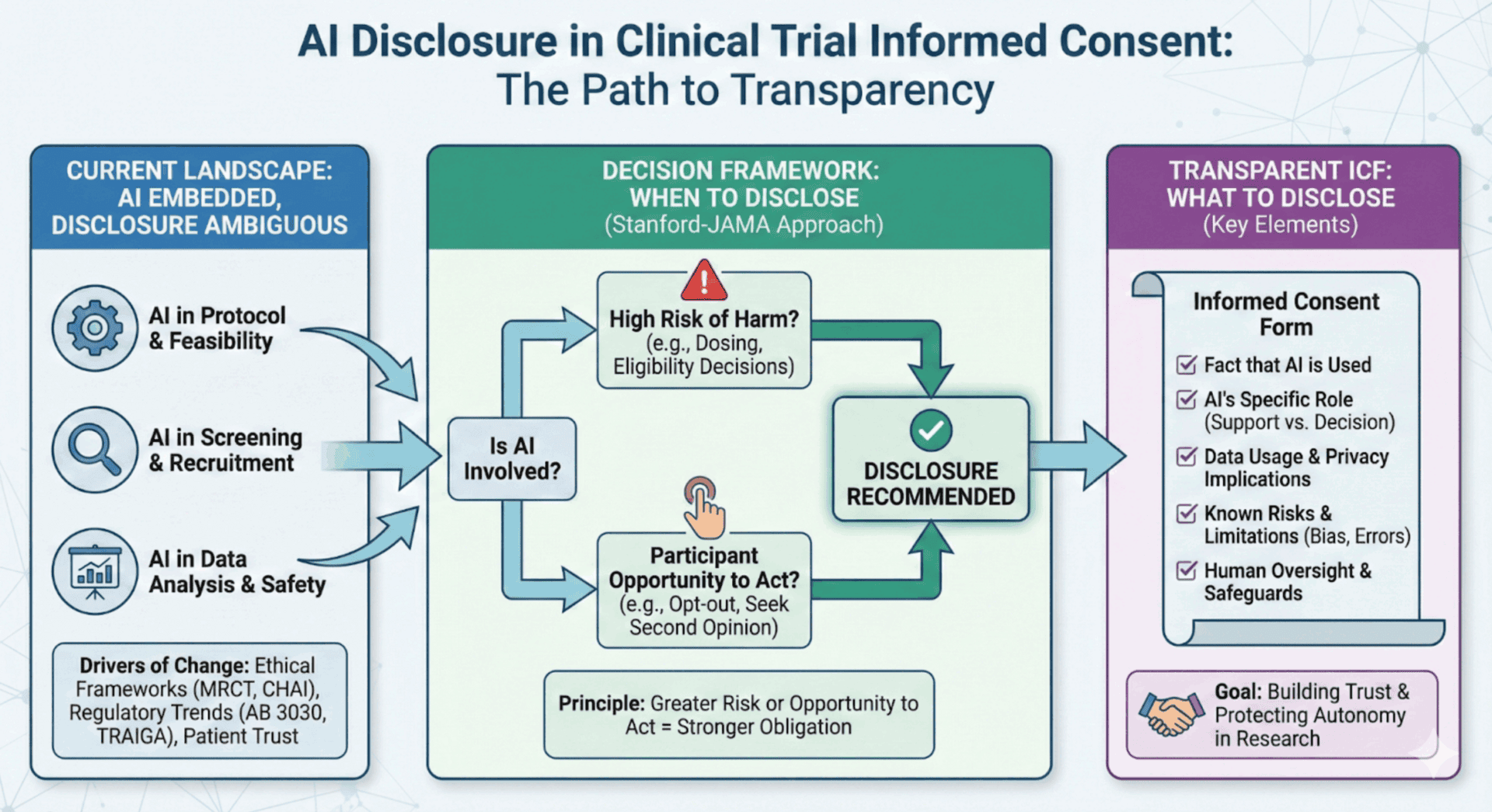

The clinical research community is at a pivotal moment. AI is already deeply embedded across the clinical trial ecosystem—from protocol optimization and site feasibility to patient recruitment and safety monitoring. Yet the guidance around when and how to disclose this use to participants has, until recently, remained frustratingly ambiguous. That’s now changing, and the direction is clear: transparency is emerging as both an ethical imperative and a practical best practice.

The Disclosure Dilemma

Consider this scenario: A sponsor uses an AI algorithm to analyze a participant’s medical records during screening. The algorithm flags the patient as potentially eligible. A study coordinator reviews and confirms the recommendation. Should the informed consent form mention the AI’s role? What about when an AI system helps generate the consent form itself, simplifying the language to improve readability? Or when an adaptive AI model is used to adjust dosing recommendations during the trial?

These aren’t hypotheticals—they’re happening now across thousands of clinical trials worldwide. And until this year, there was remarkably little authoritative guidance on what to tell participants about any of it.

The regulatory silence reflects a broader challenge: informed consent frameworks were designed before AI became a routine participant in clinical decision-making. As Harvard’s Petrie-Flom Center recently observed, informed consent in the age of AI risks becoming “symbolic—a checkbox” rather than a meaningful protection of participant autonomy. The traditional model assumed human agents making decisions that patients could understand and question. AI introduces complexity that strains this foundation.

The 2025 Guidance Landscape

The past year has brought a wave of frameworks and guidance documents that, while not creating binding legal requirements, are shaping expectations and best practices around AI disclosure in clinical research.

The MRCT Center Framework for AI in Clinical Research

In June 2025, the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center at Harvard, in collaboration with WCG, released what may be the most comprehensive resource for IRBs evaluating AI-related protocols: the Framework for Review of Clinical Research Involving AI. This toolkit provides decision trees, stage-specific guidance, and targeted ethical considerations for AI applications across the research lifecycle.

The framework addresses a critical gap: helping IRBs understand what to look for when protocols involve AI, including questions about algorithmic bias, adaptive learning, data identifiability, and the all-important issue of human oversight. While stopping short of mandating specific consent language, the framework signals that AI use should be a consideration during protocol review and, where appropriate, disclosed to participants in ways they can understand.

The MRCT Center’s broader AI and Ethical Research project explicitly calls out informed consent as a key domain where AI deployment intersects with participant rights. The message is unmistakable: if AI is involved in clinical decisions or data handling that affects participants, review bodies should be asking whether and how participants are being informed.

The Joint Commission and CHAI Guidance

In September 2025, the Joint Commission and the Coalition for Health AI (CHAI) released their landmark Guidance on the Responsible Use of AI in Healthcare (RUAIH). While focused primarily on clinical care delivery, this guidance carries important implications for clinical research, particularly given the overlap between healthcare delivery and trial operations at academic medical centers and research hospitals.

The RUAIH guidance is organized around seven elements of responsible AI use, with patient privacy and transparency occupying a central position. The guidance explicitly recommends that healthcare organizations inform patients when AI tools “directly impact their care” and that consent should be obtained “where appropriate.”

For clinical research, this principle translates naturally: if AI directly impacts participant experience, safety monitoring, or clinical decision-making within a trial, transparency is warranted. The guidance further recommends disclosures and educational tools to help consumers understand how AI is being used—a recommendation that applies equally to research participants.

The joint venture between the Joint Commission and CHAI signals an important trend: responsible AI governance is moving from academic discourse to operational guidance. A voluntary “Responsible Use of AI” certification program is forthcoming, and organizations that adopt these principles early will be better positioned when—not if—formal requirements emerge.

The Stanford-JAMA Framework for AI Disclosure

Perhaps the most actionable framework for thinking about AI disclosure emerged in July 2025, when Stanford health policy and law professors, including Michelle Mello, published a JAMA Perspective titled Ethical Obligations to Inform Patients About Use of AI Tools. Their framework proposes two primary factors for determining when disclosure is required:

- Risk of physical harm: How likely is it that an AI error could impact patient safety, and how likely is it that human intervention would catch the error before harm occurs?

- Patients’ opportunity to act: Can patients meaningfully respond to the disclosure—for example, by opting out, by exercising their own judgment over AI outputs, or by seeking a second opinion?

The framework argues that the greater the risk and /or opportunity to act, the stronger the ethical obligation to disclose. Notably, the authors recommend that disclosure decisions should be made at the organizational level, not left to individual clinicians or investigators. This approach ensures consistency and prevents ad hoc decisions that might shortchange participant rights.

For clinical research, this framework suggests that disclosure is particularly important when:

- AI is involved in eligibility determination or patient selection

- AI algorithms influence treatment assignments or dosing decisions

- AI systems process patient data in ways that create privacy or reidentification risks

- Participants could reasonably decline AI involvement if informed

The JAMA framework also emphasizes the importance of general communication with the public about how organizations use AI—a principle that could translate to trial sponsor websites, patient-facing trial registries, and institutional communications.

What Should Be Disclosed?

Drawing from the recent guidance and emerging best practices, here are the key elements that increasingly are expected to appear in informed consent when AI plays a material role:

- The type of AI involvement: Distinguish between AI that supports the process (e.g., drafting text or organizing data) and AI that drives decisions (e.g., determining eligibility or calculating dosing). The latter carries a higher ethical burden for disclosure because it directly impacts participant safety and study outcomes.

- That AI is being used: Participants should know that artificial intelligence, machine learning, or algorithmic tools are part of the research process. This need not be technical, but it should be honest and clear.

- The role AI plays: Is AI being used for screening? Data analysis? Safety monitoring? Treatment recommendations? Participants deserve context about where in the research process AI is involved and how it interacts with human decision-making.

- How participant data will be used by AI systems: Will their data be used to train AI models? Will it be processed by third-party AI systems? Are there secondary uses of data that participants should understand?

- Known limitations and risks: AI systems have limitations—including the potential for algorithmic bias, errors, and unexpected behaviors. Where material, these should be disclosed in language participants can understand.

- Safeguards and human oversight: Participants should know what protections are in place. Is there a human in the loop reviewing AI outputs? What happens if the AI produces an unexpected or concerning result?

The University of Washington’s School of Medicine IRB guidance captures this well, requiring that consent materials “clearly explain the role of AI in the study, how data will be used, describe the risks and limitations of the AI system, the safeguards that will be in place, and how any results will be returned to participants.”

The Patient Perspective

Why does this matter? Because participants want to know.

A comprehensive JAMA study found that 63% of U.S. adults want to be notified when AI is involved in their diagnosis or treatment. Sixty percent said they would feel uncomfortable if their physician relied on AI, and only one in three said they trust healthcare systems to use AI responsibly.

These numbers are sobering. They reflect a public that is aware of AI’s growing presence in healthcare—and skeptical about whether their interests are being protected. Clinical research operates on a foundation of trust, and that trust is built through transparency. Failing to disclose AI use, when participants would reasonably want to know, undermines that foundation.

A 2024 study surveying 1,000 patients in South Korea found broad support for disclosing AI use during informed consent but also revealed that preferences for information vary by gender, age, and income level. The researchers recommend that “ethical guidelines be developed for informed consent when using AI in diagnoses that go beyond mere legal requirements.” In other words, disclosure should be tailored to individual participant needs, not treated as a one-size-fits-all checkbox.

State and Federal Trends

While no federal regulation currently mandates AI disclosure in clinical trial ICFs, the trend lines are moving in that direction.

California AB 3030, effective January 2025, requires healthcare providers using generative AI in patient-facing materials to include a disclaimer indicating the content was AI-generated. Notably, AB 3030 includes exemptions for content reviewed by human providers—a standard check in clinical trials. However, forward-thinking sponsors aren’t looking for legal loopholes; they are looking at the intent of the law. The signal is clear: patients expect to know when AI is speaking to them.

Texas’s TRAIGA, effective January 2026, requires healthcare providers to disclose to patients when AI systems are used in diagnosis or treatment, with disclosure occurring before or at the time of interaction (except in emergencies).

At the federal level, the FDA’s draft guidance on AI in drug development emphasizes transparency and documentation requirements, though it focuses primarily on regulatory submissions rather than participant-level consent. The updated FDAAA 801 rules now require mandatory posting of informed consent documents for applicable clinical trials, increasing public visibility into what participants are—and aren’t—being told.

HHS’s Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) SACHRP committee has also weighed in, noting that for AI research requiring informed consent, “the nature of the risks and benefits of such research is ill-suited to the current required” standard disclosure framework. This acknowledgment of the problem suggests that updated guidance may be forthcoming.

The CHAI Imperative

For organizations navigating this landscape, the Coalition for Health AI (CHAI) offers both principles and community. CHAI is a nonprofit leading efforts to set responsible AI standards in healthcare, with members including clinicians, health systems, AI developers, and patient advocates.

CHAI’s principles emphasize transparency as a core value: organizations must “clearly disclose when, how, and where AI is being used, including model sources and known data limitations.” This extends to both patients and staff, including disclosures about how data is used and the role AI plays in decision-making.

CHAI’s model card framework for AI solutions includes a specific field for developers to indicate whether “patient informed consent or disclosure” is recommended for the use of the solution. This practical touch point helps ensure that transparency isn’t forgotten as AI tools move from development to deployment.

The Irony of AI-Improved Consent

Here’s a compelling twist in the disclosure story: AI may actually make informed consent better.

Research presented at ASCO and published this year demonstrates that AI-generated informed consent forms significantly outperform human-generated versions in understandability and actionability. One study found AI-generated ICFs achieved a perfect 100% actionability score compared to 0% for traditional consent forms. Another real-world implementation at LifeSpan Healthcare System used ChatGPT-4 to reduce their surgical consent form from a 12.6 Flesch-Kincaid reading level to 6.7—more accessible to the 54% of Americans who read below the sixth-grade level.

A separate study analyzing 798 federally funded clinical trials found that each additional Flesch-Kincaid grade level increase in consent form language was associated with a 16% increase in participant dropout rate. The message is clear: simpler consent forms lead to better-informed participants and more successful trials.

So while we’re debating whether to disclose AI use, AI is simultaneously making disclosure—and comprehension—more achievable. The tool we’re discussing can help solve the problem it creates.

Recommendations for Research Organizations

Based on the emerging consensus, here are practical steps for sponsors, sites, and IRBs:

- Conduct an AI inventory: Map where AI is used across your clinical trial operations—from protocol design through study close-out. You can’t disclose what you don’t know.

- Develop disclosure principles: Establish organizational guidelines for when AI use should be disclosed in informed consent. Use the Stanford-JAMA framework as a starting point: assess risk of harm and participants’ opportunity to act.

- Create accessible consent language: Develop template language for common AI applications that is clear, non-technical, and focused on what matters to participants. Consider using AI tools to ensure readability.

- Train your teams: Ensure investigators, coordinators, and IRB members understand when and how to address AI in protocol submissions and consent materials. The MRCT Center framework and CHAI resources provide excellent starting points.

- Engage with evolving guidance: Stay current with CHAI, Joint Commission, and regulatory developments. The landscape is evolving rapidly, and proactive organizations will be better positioned than reactive ones.

- Default to transparency: When in doubt, disclose. The risks of over-disclosure are minimal; the risks of under-disclosure—to trust, to regulatory standing, and to ethical integrity—are substantial.

The Path Forward

The question of AI disclosure in clinical research informed consent is no longer an edge case—it’s a central challenge for our field. The tools, frameworks, and proven implementations are here. Patient expectations are clear. Regulatory pressure is building.

The organizations that thrive will be those that embrace transparency proactively, not as a compliance burden but as a foundation for trust. Clinical research depends on participants’ willingness to volunteer their time, their data, and their bodies in service of scientific progress. They deserve to know when AI is part of that equation.

The conversation has shifted from “Can we use AI?” to “How do we use it responsibly?” The answer, increasingly, starts with disclosure.

Jim Wagner is CEO of The Contract Network, where AI is used responsibly under enterprise-grade security controls to help research sites and sponsors optimize clinical trial agreements and budgets. TCN’s AI implementation follows CHAI principles, maintains SOC 2 Type II compliance, and prohibits model training on customer data.